Arnold Schwarzenegger

Arnold Schwarzenegger | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

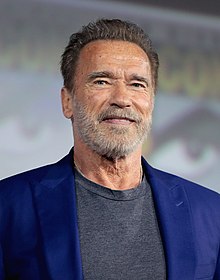

Schwarzenegger in 2019 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 38th Governor of California | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office November 17, 2003 – January 3, 2011 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lieutenant | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Gray Davis | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Jerry Brown | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman of the President's Council on Physical Fitness and Sports | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office January 22, 1990 – May 27, 1993 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Dick Kazmaier | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Arnold Alois Schwarzenegger July 30, 1947 Thal, Styria, Austria[a] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Citizenship |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Republican | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 5, including Katherine, Patrick and Joseph Baena | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parent |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Relatives | Chris Pratt (son-in-law) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Education | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupation |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

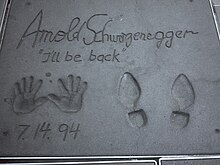

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | www | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Military service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Branch/service | Austrian Armed Forces | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years of service | 1965 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank | Wehrmann | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Unit | Belgier Barracks | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Bodybuilding and business career

|

||

Arnold Alois Schwarzenegger (/ˈʃwɔːrtsənɛɡər/ SHWORT-sə-neg-ər, Austrian German: [ˈarnɔlt ˈaːlɔʏs ˈʃvartsn̩ˌɛɡɐ] ; born July 30, 1947) is an Austrian and American actor, businessman, former politician, and retired professional bodybuilder, known for his roles in high-profile action films. He served as the 38th governor of California from 2003 to 2011.[5]

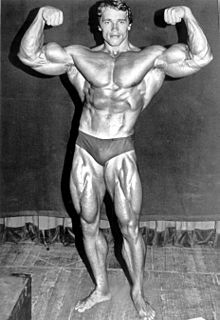

Schwarzenegger began lifting weights at age 15 and won the Mr. Universe title aged 20, and subsequently the Mr. Olympia title seven times. He is tied with Phil Heath for the joint-second number of all-time Mr. Olympia wins, behind Ronnie Coleman and Lee Haney, who are joint-first with eight wins each. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest, if not the greatest bodybuilders of all time,[6][7] and has written many books and articles about it.[8] The Arnold Sports Festival, considered the second-most important bodybuilding event after Mr. Olympia, is named after him.[9] He appeared in the bodybuilding documentary Pumping Iron (1977). After retiring from bodybuilding, he gained worldwide fame as a Hollywood action star, with his breakthrough in the sword and sorcery epic Conan the Barbarian (1982),[10] a box-office success with a sequel in 1984.[11] After playing the title character in the science fiction film The Terminator (1984), he starred in Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) and three other sequels. His other successful action films included Commando (1985), The Running Man (1987), Predator (1987), Total Recall (1990), and True Lies (1994), in addition to comedy films such as Twins (1988), Kindergarten Cop (1990) and Jingle All the Way (1996).[12] He is the founder of the film production company Oak Productions.[13]

As a registered member of the Republican Party, Schwarzenegger chaired the President's Council on Physical Fitness and Sports during most of the George H. W. Bush administration. In 2003, he was elected governor of California in a special recall election to replace Gray Davis, the governor at the time. He received 48.6 percent of the vote, 17 points ahead of the runner-up, Cruz Bustamante of the Democratic Party. He was sworn in on November 17 to serve the remainder of Davis' term, and was reelected in the 2006 gubernatorial election with an increased vote share of 55.9 percent to serve a full term.[14] In 2011 he reached his term limit as governor and returned to acting.

Schwarzenegger was nicknamed the "Austrian Oak" in his bodybuilding days, "Arnie" or "Schwarzy" during his acting career,[15] and "the Governator" (a portmanteau of "Governor" and "Terminator") during his political career. He married Maria Shriver, a niece of the former U.S. president John F. Kennedy, in 1986. They separated in 2011 after he admitted to having fathered a child with their housemaid in 1997; their divorce was finalized in 2021.[16]

Early life and education

Arnold Alois Schwarzenegger was born in Thal on July 30, 1947,[17] the second son of Gustav Schwarzenegger and his wife Aurelia (née Jadrny; 1922–1998). Gustav was the local chief of police, and after the Anschluss in 1938 joined the Nazi Party and in 1939 the Sturmabteilung (SA). In World War II, Gustav served as a military policeman in the invasions of Poland, France and the Soviet Union, including the siege of Leningrad, rising to the title of Hauptfeldwebel.[18][19] He was wounded in the Battle of Stalingrad,[20] and was discharged in 1943 following a bout of malaria. According to Holocaust scholar Michael Berenbaum, Gustav Schwarzenegger served "in theaters of the war where atrocities were committed. But there is no way to know from the documents whether he played a role."[18] Gustav's background received wide press attention during the 2003 California gubernatorial recall election in which Schwarzenegger was elected.[21]

Gustav married Aurelia on October 20, 1945; he was 38 and she was 23. According to Schwarzenegger, his parents were very strict: "Back then in Austria it was a very different world ... if we did something bad or we disobeyed our parents, the rod was not spared."[22] He grew up in a Catholic family.[23] Gustav preferred his elder son, Meinhard, over Arnold.[24] His favoritism was "strong and blatant", which stemmed from unfounded suspicion that Arnold was not his biological child.[25] Schwarzenegger says that his earliest childhood memory is of climbing into his parents' bed during a bad thunder-and-lightning storm and cuddling between his mother and father.[26] He has said, however, that his father had "no patience for listening or understanding your problems".[23] He had a good relationship with his mother, with whom he kept in touch until her death.[27]

In an interview with Fortune in 2004, Schwarzenegger told how he suffered what "would now be called child abuse" at the hands of his father: "My hair was pulled. I was hit with belts. So was the kid next door. It was just the way it was. Many of the children I've seen were broken by their parents, which was the German-Austrian mentality. They didn't want to create an individual. It was all about conforming. I was one who did not conform, and whose will could not be broken. Therefore, I became a rebel. Every time I got hit, and every time someone said, 'You can't do this,' I said, 'This is not going to be for much longer because I'm going to move out of here. I want to be rich. I want to be somebody.'"[19]

At school, Schwarzenegger was reportedly academically average but stood out for his "cheerful, good-humored, and exuberant" character.[23] He struggled with reading and was later diagnosed as being dyslexic.[28][29] Money was a problem in their household; Schwarzenegger recalled that one of the highlights of his youth was when the family bought a refrigerator.[25] His father Gustav was an athlete, and wished for his sons to become champions in Bavarian curling.[30] Influenced by his father, Schwarzenegger played several sports as a boy.[23]

Schwarzenegger began weight training in 1960 when his football coach took his team to a local gym.[17] At age 14, he chose bodybuilding over football as a career.[11][31] He later said, "I actually started weight training when I was 15, but I'd been participating in sports, like soccer, for years, so I felt that although I was slim, I was well-developed, at least enough so that I could start going to the gym and start Olympic lifting."[22] However, his official website biography claims that "at 14, he started an intensive training program with Dan Farmer, studied psychology at 15 (to learn more about the power of mind over body) and at 17, officially started his competitive career."[32] During a speech in 2001, he said, "My own plan formed when I was 14 years old. My father had wanted me to be a police officer like he was. My mother wanted me to go to trade school."[33]

Schwarzenegger took to visiting a gym in Graz, where he also frequented the local movie theaters to see films with bodybuilding idols such as Reg Park, Steve Reeves and Johnny Weissmuller.[22] When Reeves died in 2000, Schwarzenegger fondly remembered him: "As a teenager, I grew up with Steve Reeves. His remarkable accomplishments allowed me a sense of what was possible when others around me didn't always understand my dreams. Steve Reeves has been part of everything I've ever been fortunate enough to achieve." In 1961, Schwarzenegger met former Mr. Austria Kurt Marnul, who invited him to train at the gym in Graz.[17] He was so dedicated as a youngster that he broke into the local gym on weekends to train even when it was closed. "It would make me sick to miss a workout... I knew I couldn't look at myself in the mirror the next morning if I didn't do it." When asked about his first cinema experience as a boy, he replied: "I was very young, but I remember my father taking me to the Austrian theaters and seeing some newsreels. The first real movie I saw, that I distinctly remember, was a John Wayne movie."[22] In Graz, he was mentored by Alfred Gerstl, who had Jewish ancestry and later became president of the Federal Council, and befriended his son Karl.[34][35]

Schwarzenegger's brother, Meinhard, died in a car crash on May 20, 1971.[17] He was driving drunk and died instantly. Schwarzenegger did not attend his funeral. Meinhard was engaged to Erika Knapp, and they had a three-year-old son named Patrick. Schwarzenegger paid for Patrick's education and helped him to move to the U.S.[25] Schwarzenegger's father, Gustav, died of a stroke on December 13, 1972.[17] In Pumping Iron, Schwarzenegger claimed that he did not attend his father's funeral because he was training for a bodybuilding contest. Later, he and the film's producer said this story was taken from another bodybuilder to show the extremes some would go to for their sport and to make Schwarzenegger's image colder to create controversy for the film.[36] However, Barbara Baker, his first serious girlfriend, recalled that he informed her of his father's death without emotion and that he never spoke of his brother.[37] Over time, he has given at least three versions of why he was absent from his father's funeral.[25]

Schwarzenegger served in the Austrian Army in 1965 to fulfill the one year of service required at the time of all 18-year-old Austrian males.[17][32] During his army service, he won the Junior Mr. Europe contest.[31] He went AWOL during basic training so he could take part in the competition and then spent a week in military prison: "Participating in the competition meant so much to me that I didn't carefully think through the consequences." He entered another bodybuilding contest in Graz, at Steirerhof Hotel, where he placed second. He was voted "best-built man of Europe", which made him famous in bodybuilding circles. "The Mr. Universe title was my ticket to America—the land of opportunity, where I could become a star and get rich."[33] Schwarzenegger made his first plane trip in 1966, attending the NABBA Mr. Universe competition in London.[32] He placed second in the Mr. Universe competition, not having the muscle definition of American winner Chester Yorton.[32]

Charles "Wag" Bennett, one of the judges at the 1966 competition, was impressed with Schwarzenegger and offered to coach him. As Schwarzenegger had little money, Bennett invited him to stay in his crowded family home above one of his two gyms in Forest Gate, London. Yorton's leg definition had been judged superior, and Schwarzenegger, under a training program devised by Bennett, concentrated on improving his. Staying in the East End of London helped Schwarzenegger improve his rudimentary English.[38][39] Living with the Bennetts also changed him as a person: "Being with them made me so much more sophisticated. When you're the age I was then, you're always looking for approval, for love, for attention and also for guidance. At the time, I wasn't really aware of that. But now, looking back, I see that the Bennett family fulfilled all those needs. Especially my need to be the best in the world. To be recognized and to feel unique and special. They saw that I needed that care and attention and love."[40]

Also in 1966, at Bennett's home, Schwarzenegger had the opportunity to meet childhood idol Reg Park, who became his friend and mentor.[40][41] The training paid off and, in 1967, Schwarzenegger won the title for the first time, becoming the youngest ever Mr. Universe at age 20.[32] He would go on to win the title another three times.[31] He then returned to Munich, where he attended business school and worked at Rolf Putziger's gym, where he worked and trained from 1966 to 1968 before returning to London in 1968 to win his next Mr. Universe title.[32] He frequently told Roger C. Field, his English coach and friend in Munich at the time, "I'm going to become the greatest actor!"[42]

Schwarzenegger, who dreamed of moving to the US since age ten, and saw bodybuilding as his avenue of opportunity,[43] realized his dream by moving to the US in October 1968 at age 21, speaking little English.[31][17] There he trained at Gold's Gym in Venice, Los Angeles, California, under Joe Weider's supervision. From 1970 to 1974, one of Schwarzenegger's weight training partners was Ric Drasin, a professional wrestler who designed the original Gold's Gym logo in 1973.[44] Schwarzenegger also became good friends with professional wrestler Superstar Billy Graham. In 1970, at age 23, Schwarzenegger captured his first Mr. Olympia title in New York, and would go on to win the title seven times.[32]

The immigration law firm Siskind & Susser has stated that Schwarzenegger may have been an illegal immigrant at some point in the late 1960s or early 1970s because of violations in the terms of his visa.[45] LA Weekly said in 2002 that Schwarzenegger was "the most famous US immigrant", who "overcame a thick Austrian accent and transcended the unlikely background of bodybuilding to become the biggest movie star in the world in the 1990s".[43]

In 1977, Schwarzenegger's autobiography and weight-training guide, Arnold: The Education of a Bodybuilder, was a huge success.[17] In 1977, he posed for the gay magazine After Dark.[46][47] After taking an assortment of courses at Santa Monica College in California (including English classes), as well as further upper division classes at the University of California, Los Angeles as part of UCLA's extension program, he accumulated enough credits to be "within striking distance" of graduation. In 1979, he enrolled in the University of Wisconsin–Superior as a distance education student, completing most of his coursework by correspondence and flying out to Superior to meet professors and take final exams. In May 1980, he formally graduated and earned his bachelor's degree in business administration and marketing. He received his United States citizenship in 1983.[48] He received an honorary degree from Stockton University in 2023.[49]

Bodybuilding career

Schwarzenegger is considered among the most important figures in the history of bodybuilding,[9] and his legacy is commemorated in the Arnold Classic annual bodybuilding competition. He has remained a prominent face in bodybuilding long after his retirement, in part because of his ownership of gyms and fitness magazines. He has presided over numerous contests and awards shows.

For many years, he wrote a monthly column for the bodybuilding magazines Muscle & Fitness and Flex. Shortly after being elected governor, he was appointed the executive editor of both magazines, in a largely symbolic capacity. The magazines agreed to donate $250,000 a year to the Governor's various physical fitness initiatives. When the deal, including the contract that gave Schwarzenegger at least $1 million a year, was made public in 2005, many criticized it as being a conflict of interest since the governor's office made decisions concerning regulation of dietary supplements in California.[50] Consequently, Schwarzenegger relinquished the executive editor role in 2005.[50] American Media Inc., which owns Muscle & Fitness and Flex, announced in March 2013 that Schwarzenegger had accepted their renewed offer to be executive editor of the magazines.[50]

One of the first competitions he won was the Junior Mr. Europe contest in 1965.[17] He won Mr. Europe the following year, at age 19.[17][32] He would go on to compete in many bodybuilding contests, and win most of them. His bodybuilding victories included five Mr. Universe wins (4 – NABBA [England], 1 – IFBB [USA]), and seven Mr. Olympia wins, a record which would stand until Lee Haney won his eighth consecutive Mr. Olympia title in 1991.

Schwarzenegger continues to work out. When asked about his personal training during the 2011 Arnold Classic he said that he was still working out a half an hour with weights every day.[51]

Powerlifting/weightlifting

During Schwarzenegger's early years in bodybuilding, he also competed in several Olympic weightlifting and powerlifting contests. Schwarzenegger's first professional competition was in 1963[52] and he won two weightlifting contests in 1964 and 1965, as well as two powerlifting contests in 1966 and 1968.[4]

In 1967, Schwarzenegger won the Munich stone-lifting contest, in which a stone weighing 508 German pounds (254 kg / 560 lb) is lifted between the legs while standing on two footrests.

Personal records

- Clean and press – 264 lb (120 kg)[4]

- Snatch – 243 lb (110 kg)[4]

- Clean and jerk – 298 lb (135 kg)[4]

- Squat – 545 lb (247 kg)[4]

- Bench press – 520 lb (240 kg)[53][54]

- Deadlift – 683 lb (310 kg)[4]

Mr. Olympia

Schwarzenegger's goal was to become the greatest bodybuilder in the world, which meant becoming Mr. Olympia.[17][32] His first attempt was in 1969, when he lost to three-time champion Sergio Oliva. However, Schwarzenegger came back in 1970 and won the competition, making him the youngest ever Mr. Olympia at the age of 23, a record he still holds to this day.[32]

He continued his winning streak in the 1971–1974 competitions.[32] He also toured different countries selling vitamins, as in Helsinki, Finland in 1972, when he lived at the YMCA Hotel Hospiz (nowadays Hotel Arthur[55]) on Vuorikatu and presented vitamin pills at the Stockmann shopping center.[56][57] In 1975, Schwarzenegger was once again in top form, and won the title for the sixth consecutive time,[32] beating Franco Columbu. After the 1975 Mr. Olympia contest, Schwarzenegger announced his retirement from professional bodybuilding.[32]

Months before the 1975 Mr. Olympia contest, filmmakers George Butler and Robert Fiore persuaded Schwarzenegger to compete and film his training in the bodybuilding documentary called Pumping Iron. Schwarzenegger had only three months to prepare for the competition, after losing significant weight to appear in the film Stay Hungry with Jeff Bridges. Although significantly taller and heavier, Lou Ferrigno proved not to be a threat, and a lighter-than-usual Schwarzenegger convincingly won the 1975 Mr. Olympia.

Schwarzenegger came out of retirement, however, to compete in the 1980 Mr. Olympia.[17] Schwarzenegger was training for his role in Conan, and he got into such good shape because of the running, horseback riding and sword training, that he decided he wanted to win the Mr. Olympia contest one last time. He kept this plan a secret in the event that a training accident would prevent his entry and cause him to lose face. Schwarzenegger had been hired to provide color commentary for network television when he announced at the eleventh hour that, while he was there, "Why not compete?" Schwarzenegger ended up winning the event with only seven weeks of preparation. Having been declared Mr. Olympia for a seventh time, Schwarzenegger then officially retired from competition. This victory (subject of the documentary The Comeback) was highly controversial, though, as fellow competitors and many observers felt that his lack of muscle mass (especially in his thighs) and subpar conditioning should have precluded him from winning against a very competitive lineup that year.[9][58] Mike Mentzer, in particular, felt cheated and withdrew from competitive bodybuilding after that contest.[59][58]

List of competitions

| Year | Competition[60] | Location | Result and notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1965 | Junior Mr. Europe | Germany | 1st |

| 1966 | Best Built Man of Europe | Germany | 1st |

| 1966 | Mr. Europe | Germany | 1st |

| 1966 | International Powerlifting Championship | Germany | 1st |

| 1966 | NABBA Mr. Universe amateur | London | 2nd to Chet Yorton |

| 1967 | NABBA Mr. Universe amateur | London | 1st |

| 1968 | NABBA Mr. Universe professional | London | 1st |

| 1968 | German Powerlifting Championship | Germany | 1st |

| 1968 | IFBB Mr. International | Mexico | 1st |

| 1968 | IFBB Mr. Universe | Florida | 2nd to Frank Zane |

| 1969 | IFBB Mr. Universe amateur | New York | 1st |

| 1969 | NABBA Mr. Universe professional | London | 1st |

| 1969 | Mr. Olympia | New York | 2nd to Sergio Oliva |

| 1970 | NABBA Mr. Universe professional | London | 1st (defeated his idol Reg Park) |

| 1970 | AAU Mr. World | Columbus, Ohio | 1st (defeated Sergio Oliva for the first time) |

| 1970 | Mr. Olympia | New York | 1st |

| 1971 | Mr. Olympia | Paris | 1st |

| 1972 | Mr. Olympia | Essen, Germany | 1st |

| 1973 | Mr. Olympia | New York | 1st |

| 1974 | Mr. Olympia | New York | 1st |

| 1975 | Mr. Olympia | Pretoria, South Africa | 1st (subject of the documentary Pumping Iron) |

| 1980 | Mr. Olympia | Sydney | 1st (subject of the documentary The Comeback) |

Statistics

- Height: 6 ft 2 in (1.88 m)

- Contest weight: 235 lb (107 kg)—the lightest in 1980 Mr. Olympia: around 225 lb (102 kg), the heaviest in 1974 Mr. Olympia: around 250 lb (110 kg)[61]

- Off-season weight: 260 lb (118 kg)

- Chest: 57 in (140 cm)

- Waist: 33 in (84 cm)

- Arms: 22 in (56 cm)

- Thighs: 29.5 in (75 cm)

- Calves: 20 in (51 cm)[62]

Steroid use

Schwarzenegger has acknowledged using performance-enhancing anabolic steroids while they were legal, writing in 1977 that "steroids were helpful to me in maintaining muscle size while on a strict diet in preparation for a contest. I did not use them for muscle growth, but rather for muscle maintenance when cutting up."[63] He has called the drugs "tissue building".[64]

In 1999, Schwarzenegger sued Willi Heepe, a German doctor who publicly predicted his early death on the basis of a link between his steroid use and later heart problems. Since the doctor never examined him personally, Schwarzenegger collected a US$10,000 libel judgment against him in a German court.[65] In 1999, Schwarzenegger also sued and settled with Globe, a U.S. tabloid which had made similar predictions about the bodybuilder's future health.[66]

Acting career

1970–1981: Early roles

Schwarzenegger wanted to move from bodybuilding into acting, finally achieving it when he was chosen to play the title role in Hercules in New York (1970). Credited under the stage name "Arnold Strong", his accent in the film was so thick that his lines were dubbed after production.[31] His second film appearance was as a mob hitman in The Long Goodbye (1973), which was followed by a much more significant part in the film Stay Hungry (1976), for which he won the Golden Globe Award for New Star of the Year – Actor. Schwarzenegger has discussed his early struggles in developing his acting career: "It was very difficult for me in the beginning – I was told by agents and casting people that my body was 'too weird', that I had a funny accent, and that my name was too long. You name it, and they told me I had to change it. Basically, everywhere I turned, I was told that I had no chance."[22]

Schwarzenegger drew attention and boosted his profile in the bodybuilding film Pumping Iron (1977),[11][31] elements of which were dramatized. In 1991, he purchased the rights to the film, its outtakes, and associated still photography.[67] In 1977, he made guest appearances in single episodes of the ABC sitcom The San Pedro Beach Bums and the ABC police procedural The Streets of San Francisco. Schwarzenegger auditioned for the title role of The Incredible Hulk, but did not win the role because of his height. Later, Lou Ferrigno got the part of Dr. David Banner's alter ego. Schwarzenegger appeared with Kirk Douglas and Ann-Margret in the 1979 comedy The Villain. In 1980, he starred in a biographical film of the 1950s actress Jayne Mansfield as Mansfield's husband, Mickey Hargitay.

1982–2003: Breakthrough and established action star

Schwarzenegger's breakthrough film was the sword and sorcery epic Conan the Barbarian in 1982, which was a box-office hit.[11] This was followed by a sequel, Conan the Destroyer, in 1984, although it was not as successful as its predecessor.[68] In 1983, Schwarzenegger starred in the promotional video Carnival in Rio.[69] In 1984, he made his first appearance as the eponymous character in James Cameron's science fiction action film The Terminator.[11][31][70] It has been called his acting career's signature role.[71] Following this, Schwarzenegger made another sword and sorcery film, Red Sonja, in 1985.[68] During the 1980s, audiences had an appetite for action films, with both Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone becoming international stars.[31] During the Schwarzenegger-Stallone rivalry they attacked each other in the press, and tried to surpass the other with more on-screen killings and larger weapons.[72] Schwarzenegger's roles reflected his sense of humor, separating him from more serious action hero films. He made a number of successful action films in the 1980s, such as Commando (1985), Raw Deal (1986), The Running Man (1987), Predator (1987), and Red Heat (1988).

Twins (1988), a comedy with Danny DeVito, also proved successful. Total Recall (1990) netted Schwarzenegger $10 million (equivalent to $23.3 million today) and 15% of the film's gross. A science fiction script, the film was based on the Philip K. Dick short story "We Can Remember It for You Wholesale". Kindergarten Cop (1990) reunited him with director Ivan Reitman, who directed him in Twins. Schwarzenegger had a brief foray into directing, first with a 1990 episode of the TV series Tales from the Crypt, "The Switch",[73] and then with the 1992 telemovie Christmas in Connecticut.[74] He has not directed since.

Schwarzenegger's commercial peak was his return as the title character in Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991), which was the highest-grossing film of the year. Film critic Roger Ebert commented that "Schwarzenegger's genius as a movie star is to find roles that build on, rather than undermine, his physical and vocal characteristics."[75] In 1993, the National Association of Theatre Owners named him the "International Star of the Decade".[17] His next film project, the 1993 self-aware action comedy spoof Last Action Hero, was released opposite Jurassic Park, and did not do well at the box office. His next film, the comedy drama True Lies (1994), was a popular spy film and saw Schwarzenegger reunited with James Cameron.

That same year, the comedy Junior was released, the last of Schwarzenegger's three collaborations with Ivan Reitman and again co-starring Danny DeVito. This film brought him his second Golden Globe nomination, this time for Best Actor – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy. It was followed by the action thriller Eraser (1996), the Christmas comedy Jingle All The Way (1996), and the comic book-based Batman & Robin (1997), in which he played the supervillain Mr. Freeze. This was his final film before taking time to recuperate from a back injury. Following the critical failure of Batman & Robin, his film career and box office prominence went into decline. He returned with the supernatural thriller End of Days (1999), later followed by the action films The 6th Day (2000) and Collateral Damage (2002), both of which failed to do well at the box office. In 2003, he made his third appearance as the title character in Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines, which went on to earn over $150 million domestically (equivalent to $248 million today).[76]

In tribute to Schwarzenegger in 2002, Forum Stadtpark, a local cultural association, proposed plans to build a 25-meter-tall (80 ft) Terminator statue in a park in central Graz. Schwarzenegger reportedly said he was flattered, but thought the money would be better spent on social projects and the Special Olympics.[77]

2004–2010: Retirement

His film appearances after becoming Governor of California included a three-second cameo appearance in The Rundown and the 2004 remake of Around the World in 80 Days. In 2005, he appeared as himself in the film The Kid & I. He voiced Baron von Steuben in the Liberty's Kids episode "Valley Forge". He had been rumored to be appearing in Terminator Salvation as the original T-800; he denied his involvement,[78] but he ultimately did appear briefly via his image being inserted into the movie from stock footage of the first Terminator film.[79][80] Schwarzenegger appeared in Sylvester Stallone's The Expendables (2010), where he made a cameo appearance.

2011–present: Return to acting

In January 2011, just weeks after leaving office in California, Schwarzenegger announced that he was reading several new scripts for future films, one of them being the World War II action drama With Wings as Eagles, written by Randall Wallace, based on a true story.[81][82]

On March 6, 2011, at the Arnold Seminar of the Arnold Classic, Schwarzenegger revealed that he was being considered for several films, including sequels to The Terminator and remakes of Predator and The Running Man, and that he was "packaging" a comic book character.[83] The character was later revealed to be the Governator, star of the comic book and animated series of the same name. Schwarzenegger inspired the character and co-developed it with Stan Lee, who would have produced the series. Schwarzenegger would have voiced the Governator.[84][85][86][87]

On May 20, 2011, Schwarzenegger's entertainment counsel announced that all film projects currently in development were being halted: "Schwarzenegger is focusing on personal matters and is not willing to commit to any production schedules or timelines."[88] On July 11, 2011, it was announced that Schwarzenegger was considering a comeback film, despite legal problems related to his divorce.[89] He starred in The Expendables 2 (2012) as Trench Mauser,[90] and starred in The Last Stand (2013), his first leading role in 10 years, and Escape Plan (2013), his first co-starring role alongside Sylvester Stallone. He starred in Sabotage, released in March 2014, and returned as Trench Mauser in The Expendables 3, released in August 2014. He starred in the fifth Terminator film Terminator Genisys in 2015.[11][31][70][91] He then planned to reprise his role as Conan the Barbarian in The Legend of Conan,[92][93] later renamed Conan the Conqueror. [94] However, in April 2017, producer Chris Morgan stated that Universal had dropped the project, although there was a possibility of a TV show. The story of the film was supposed to be set 30 years after the first, with some inspiration from Clint Eastwood's Unforgiven.[95]

In September 2015, the media announced that Schwarzenegger was to replace Donald Trump as host of The New Celebrity Apprentice.[96] This show, the 15th season of The Apprentice, aired during the 2016–2017 TV season. In the show, he used the phrases "you're terminated" and "get to the choppa", which are quotes from some of his famous roles (The Terminator and Predator, respectively), when firing the contestants.[97][98] In March 2017, following repeated criticisms from Trump, Schwarzenegger announced that he would not return for another season on the show. He also reacted to Trump's remarks in January 2017 via Instagram: "Hey, Donald, I have a great idea. Why don't we switch jobs? You take over TV because you're such an expert in ratings, and I take over your job, and then people can finally sleep comfortably again."[99]

In August 2016, his filming of action-comedy Killing Gunther was temporarily interrupted by bank robbers near the filming location in Surrey, British Columbia.[100] The film was released in September 2017. He was announced to star and produce in a film about the ruins of Sanxingdui called The Guest of Sanxingdui as an ambassador.[101]

On February 6, 2018, Amazon Studios announced they were working with Schwarzenegger to develop a new series, Outrider, in which he will star and executive produce. The western-drama set in the Oklahoma Indian Territory in the late 19th century will follow a deputy (portrayed by Schwarzenegger) who is tasked with apprehending a legendary outlaw in the wilderness, but is forced to partner with a ruthless Federal Marshal to make sure justice is properly served. The series would also mark as Schwarzenegger's first major scripted TV role.[102]

Schwarzenegger returned to the Terminator franchise with Terminator: Dark Fate, which was released on November 1, 2019. It was produced by the series' co-creator James Cameron, who directed him previously in the first two films in the series and in True Lies.[103][104] It was shot in Almería, Hungary and the US.[105]

Political career

Early politics

Schwarzenegger has been a registered Republican for many years. When he was an actor, his political views were always well known as they contrasted with those of many other prominent Hollywood stars, who are generally considered to be a left-wing and Democratic-leaning community. At the 2004 Republican National Convention, Schwarzenegger gave a speech and explained that he was a Republican because he believed the Democrats of the 1960s sounded too much like Austrian socialists.[106]

I finally arrived here in 1968. What a special day it was. I remember I arrived here with empty pockets but full of dreams, full of determination, full of desire. The presidential campaign was in full swing. I remember watching the Nixon–Humphrey presidential race on TV. A friend of mine who spoke German and English translated for me. I heard Humphrey saying things that sounded like socialism, which I had just left. But then I heard Nixon speak. He was talking about free enterprise, getting the government off your back, lowering the taxes and strengthening the military. Listening to Nixon speak sounded more like a breath of fresh air. I said to my friend, I said, "What party is he?" My friend said, "He's a Republican." I said, "Then I am a Republican." And I have been a Republican ever since.

In 1985, Schwarzenegger appeared in "Stop the Madness", an anti-drug music video sponsored by the Reagan administration. He first came to wide public notice as a Republican during the 1988 presidential election, accompanying then–Vice President George H. W. Bush at a campaign rally.[107]

Schwarzenegger famously introduced the first episode of the 1990 Milton Friedman hosted PBS series Free to Choose stating:

I truly believe that the series has changed my life, and when you have such a powerful experience as that, I think you shouldn't keep it to yourself, so I wanted to share it with you. Being 'free to choose' for me means being free to make your own decisions, free to live your own life, pursue your own goals, chase your own rainbow without the government breathing down on your neck or standing on your shoes. For me that meant coming here to America, because I came from a socialistic country where the government controls the economy. It's a place where you can hear 18-year-old kids already talking about their pension. But me, I wanted more. I wanted to be the best. Individualism like that is incompatible with socialism. So I felt I had to come to America.[108][109]

Schwarzenegger goes on to tell of how he and his then wife Maria Shriver were in Palm Springs preparing to play a game of mixed doubles when Milton Friedman's famous show came on the television. Schwarzenegger recalls that while watching Friedman's Free to Choose, Schwarzenegger, "...recognized Friedman from the study of my own degree in economics, but I didn't know I was watching Free to Choose... it knocked me out. Dr. Friedman expressed, validated and explained everything I ever thought or experienced or observed about the way the economy works, and I guess I was really ready to hear it."[109] Numerous critics state that Schwarzenegger strayed from much of Friedman's economic ways of thinking in later years, especially upon being elected Governor of California from 2003 through 2011.[110][111]

Schwarzenegger's first political appointment was as chairman of the President's Council on Physical Fitness and Sports, on which he served from 1990 to 1993.[17] He was nominated by the then-President Bush, who dubbed him "Conan the Republican". He later served as chairman for the California Governor's Council on Physical Fitness and Sports under Governor Pete Wilson.

Between 1993 and 1994, Schwarzenegger was a Red Cross ambassador (a ceremonial role fulfilled by celebrities), recording several television and radio public service announcements to donate blood.

In an interview with Talk magazine in late 1999, Schwarzenegger was asked if he thought of running for office. He replied, "I think about it many times. The possibility is there because I feel it inside." The Hollywood Reporter claimed shortly after that Schwarzenegger sought to end speculation that he might run for governor of California. Following his initial comments, Schwarzenegger said, "I'm in show business – I am in the middle of my career. Why would I go away from that and jump into something else?"[112]

Governor of California

Schwarzenegger announced his candidacy in the 2003 California recall election for Governor of California on the August 6, 2003, episode of The Tonight Show with Jay Leno.[31] Schwarzenegger had the most name recognition in a crowded field of candidates, but he had never held public office and his political views were unknown to most Californians. His candidacy immediately became national and international news, with media outlets dubbing him the "Governator" (referring to The Terminator movies, see above) and "The Running Man" (the name of another one of his films), and calling the recall election "Total Recall" (another movie starring Schwarzenegger). Schwarzenegger declined to participate in several debates with other recall replacement candidates, and appeared in only one debate on September 24, 2003.[113]

On October 7, 2003, the recall election resulted in Governor Gray Davis being removed from office with 55.4% of the Yes vote in favor of a recall. Schwarzenegger was elected Governor of California under the second question on the ballot with 48.6% of the vote to choose a successor to Davis. Schwarzenegger defeated Democrat Cruz Bustamante, fellow Republican Tom McClintock, and others. His nearest rival, Bustamante, received 31% of the vote. In total, Schwarzenegger won the election by about 1.3 million votes. Under the regulations of the California Constitution, no runoff election was required. Schwarzenegger was the second foreign-born governor of California after Irish-born Governor John G. Downey in 1862.

Schwarzenegger is a moderate Republican.[114] He says he is fiscally conservative and socially liberal.[115] On the issue of abortion, he describes himself as pro-choice, but supports parental notification for minors and a ban on partial-birth abortion.[116] He has supported gay rights, such as domestic partnerships, and he performed a same-sex marriage as governor.[117] However, Schwarzenegger vetoed bills that would have legalized same-sex marriage in California in 2005 and 2007.[118][119] He additionally vetoed two bills that would have implemented a single-payer health care system in California in 2006[120][121] and 2008,[122] respectively.

Schwarzenegger was entrenched in what he considered to be his mandate in cleaning up political gridlock. Building on a catchphrase from the sketch "Hans and Franz" from Saturday Night Live (which partly parodied his bodybuilding career), Schwarzenegger called the Democratic State politicians "girlie men".[123]

Schwarzenegger's early victories included repealing an unpopular increase in the vehicle registration fee as well as preventing driver's licenses from being given out to illegal immigrants, but later he began to feel the backlash when powerful state unions began to oppose his various initiatives. Key among his reckoning with political realities was a special election he called in November 2005, in which four ballot measures he sponsored were defeated. Schwarzenegger accepted personal responsibility for the defeats and vowed to continue to seek consensus for the people of California. He later commented that "no one could win if the opposition raised 160 million dollars to defeat you". The U.S. Supreme Court later found the public employee unions' use of compulsory fundraising during the campaign had been illegal in Knox v. Service Employees International Union, Local 1000.[124]

Schwarzenegger, against the advice of fellow Republican strategists, appointed a Democrat, Susan Kennedy, as his Chief of Staff. He gradually moved towards a more politically moderate position, determined to build a winning legacy with only a short time to go until the next gubernatorial election.

Schwarzenegger ran for re-election against Democrat Phil Angelides, the California State Treasurer, in the 2006 elections, held on November 7, 2006. Despite a poor year nationally for the Republican party, Schwarzenegger won re-election with 56.0% of the vote compared with 38.9% for Angelides, a margin of well over 1 million votes.[125] Around this time, many commentators saw Schwarzenegger as moving away from the right and towards the center of the political spectrum. After hearing a speech by Schwarzenegger at the 2006 Martin Luther King Jr. Day breakfast, in which Schwarzenegger said, in part "How wrong I was when I said everyone has an equal opportunity to make it in America ... the state of California does not provide [equal] education for all of our children", San Francisco mayor and future governor of California Gavin Newsom said: "He's becoming a Democrat ... He's running back, not even to the center. I would say center-left."[126]

Some speculated that Schwarzenegger might run for the United States Senate in 2010, as his governorship would be term-limited by that time. Such rumors turned out to be false.[127][128]

Wendy Leigh, who wrote an unofficial biography on Schwarzenegger, claims he plotted his political rise from an early age using the movie business and bodybuilding as the means to escape a depressing home.[24] Leigh portrays Schwarzenegger as obsessed with power and quotes him as saying, "I wanted to be part of the small percentage of people who were leaders, not the large mass of followers. I think it is because I saw leaders use 100% of their potential – I was always fascinated by people in control of other people."[24] Schwarzenegger has said that it was never his intention to enter politics, but he says, "I married into a political family. You get together with them and you hear about policy, about reaching out to help people. I was exposed to the idea of being a public servant and Eunice and Sargent Shriver became my heroes."[43] Eunice Kennedy Shriver was the sister of John F. Kennedy, and mother-in-law to Schwarzenegger; Sargent Shriver is husband to Eunice and father-in-law to Schwarzenegger.

Schwarzenegger cannot run for U.S. president as he is not a natural-born citizen of the United States. Schwarzenegger is a dual Austrian and United States citizen.[129] He has held Austrian citizenship since birth and U.S. citizenship since becoming naturalized in 1983. Being Austrian and thus European, he was able to win the 2007 European Voice campaigner of the year award for taking action against climate change with the California Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006 and plans to introduce an emissions trading scheme with other US states and possibly with the EU.[130]

Because of his personal wealth from his acting career, Schwarzenegger did not accept his governor's salary of $175,000 per year.[131]

Schwarzenegger's endorsement in the Republican primaries of the 2008 presidential election was highly sought; despite being good friends with candidates Rudy Giuliani and Senator John McCain, Schwarzenegger remained neutral throughout 2007 and early 2008. Giuliani dropped out of the presidential race on January 30, 2008, largely because of a poor showing in Florida, and endorsed McCain. Later that night, Schwarzenegger was in the audience at a Republican debate at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in California. The following day, he endorsed McCain, joking, "It's Rudy's fault!" (in reference to his friendships with both candidates and that he could not make up his mind). Schwarzenegger's endorsement was thought to be a boost for Senator McCain's campaign; both spoke about their concerns for the environment and economy.[132]

In its April 2010 report, Progressive ethics watchdog group Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington named Schwarzenegger one of 11 "worst governors" in the United States because of various ethics issues throughout Schwarzenegger's term as governor.[133][134]

Governor Schwarzenegger played a significant role in opposing Proposition 66, a proposed amendment of the Californian Three Strikes Law, in November 2004. This amendment would have required the third felony to be either violent or serious to mandate a 25-years-to-life sentence. In the last week before the ballot, Schwarzenegger launched an intense campaign[135] against Proposition 66.[136] He stated that "it would release 26,000 dangerous criminals and rapists".[137]

Although he began his tenure as governor with record high approval ratings (as high as 65% in May 2004),[138] he left office with a near-record low 23%,[139] only one percent higher than that of Gray Davis, his predecessor, when he was recalled in October 2003.[140]

Death of Luis Santos

In May 2010, Esteban Núñez pleaded guilty to voluntary manslaughter and was sentenced to 16 years in prison for the death of Luis Santos. Núñez is the son of Fabian Núñez, then California Assembly Speaker of the House and a close friend and staunch political ally of then governor Schwarzenegger.[141][142][143][144]

As a personal favor to "a friend", just hours before he left office, and as one of his last official acts, Schwarzenegger commuted Núñez's sentence by more than half, to seven years.[143][145][146] He believed that Núñez's sentence was "excessive" in comparison with the same prison term imposed on Ryan Jett, the man who fatally stabbed Santos.[147] Against protocol, Schwarzenegger did not inform Santos' family or the San Diego County prosecutors about the commutation. They learned about it in a call from a reporter.[146]

The Santos family, along with the San Diego district attorney, sued to stop the commutation, claiming that it violated Marsy's Law. In September 2012, Sacramento County superior court judge Lloyd Connelly stated, "Based on the evidentiary records before this court involving this case, there was an abuse of discretion... This was a distasteful commutation. It was repugnant to the bulk of the citizenry of this state." However, Connelly ruled that Schwarzenegger remained within his executive powers as governor.[141] Subsequently, as a direct result of the way the commutation was handled, Governor Jerry Brown signed a bipartisan bill that allows offenders' victims and their families to be notified at least 10 days before any commutations.[148] Núñez was released from prison after serving less than six years.[149]

Allegations of sexual misconduct

During his initial campaign for governor in 2003, allegations of sexual and personal misconduct were raised against Schwarzenegger.[150] Within the last five days before the election, news reports appeared in the Los Angeles Times recounting decades-old allegations of sexual misconduct from six individual women.[151][150] Schwarzenegger responded to the allegations in 2004 admitting that he has "behaved badly sometimes" and apologized, but also stated that "a lot of [what] you see in the stories is not true".[152] One of the women who came forward was British television personality Anna Richardson, who settled a libel lawsuit in August 2006 against Schwarzenegger; his top aide, Sean Walsh; and his publicist, Sheryl Main.[153] A joint statement read: "The parties are content to put this matter behind them and are pleased that this legal dispute has now been settled."[153][154] In 2023, Schwarzenegger revisited the issue while promoting his new three-part biographical documentary on Netflix called Arnold. Schwarzenegger stated that he was "totally wrong".[155]

Marijuana use

During this time a 1977 interview in adult magazine Oui gained attention, in which Schwarzenegger discussed using substances such as marijuana.[156] Schwarzenegger is shown smoking a marijuana joint after winning Mr. Olympia in 1975 in the documentary film Pumping Iron (1977). In an interview with GQ magazine in October 2007, Schwarzenegger said, "[Marijuana] is not a drug. It's a leaf. My drug was pumping iron, trust me."[157] His spokesperson later said the comment was meant to be a joke.[157]

Citizenship

Schwarzenegger became a naturalized U.S. citizen on September 17, 1983.[158] Shortly before he gained his citizenship, he asked the Austrian authorities for the right to keep his Austrian citizenship, as Austria does not usually allow dual citizenship. His request was granted, and he retained his Austrian citizenship.[159]

In 2005, Peter Pilz, a member of the Austrian Parliament from the Austrian Green Party, unsuccessfully advocated for Parliament to revoke Schwarzenegger's Austrian citizenship under Article 33 of the Austrian Citizenship Act, which states: "A citizen, who is in the public service of a foreign country, shall be deprived of his citizenship if he heavily damages the reputation or the interests of the Austrian Republic.". Pilz felt that Schwarzenegger's decision not to intervene in the executions of Donald Beardslee and Stanley Williams had done so.[129] The death penalty in Austria had been abolished in 1968.

Environmental record

On September 27, 2006, Schwarzenegger signed the Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006, creating the nation's first cap on greenhouse gas emissions. The law set new regulations on the amount of emissions utilities, refineries, and manufacturing plants are allowed to release into the atmosphere. Schwarzenegger also signed a second global warming bill that prohibits large utilities and corporations in California from making long-term contracts with suppliers who do not meet the state's greenhouse gas emission standards. The two bills are part of a plan to reduce California's emissions by 25 percent to 1990s levels by 2020. In 2005, Schwarzenegger issued an executive order calling to reduce greenhouse gases to 80 percent below 1990 levels by 2050.[160]

Schwarzenegger signed another executive order on October 17, 2006, allowing California to work with the Northeast's Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative. They plan to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by issuing a limited amount of carbon credits to each power plant in participating states. Any power plants that exceed emissions for the number of carbon credits will have to purchase more credits to cover the difference. The plan took effect in 2009.[161] In addition to using his political power to fight global warming, the governor has taken steps at his home to reduce his personal carbon footprint. Schwarzenegger has adapted one of his Hummers to run on hydrogen and another to run on biofuels. He has also installed solar panels to heat his home.[162]

In respect for his contribution to the direction of the US motor industry, Schwarzenegger was invited to open the 2009 SAE World Congress in Detroit on April 20, 2009.[163]

In 2011, Schwarzenegger founded the R20 Regions of Climate Action to develop a sustainable, low-carbon economy.[164] In 2017, he joined French President Emmanuel Macron in calling for the adoption of a Global Pact for the Environment.[165] In 2017, Schwarzenegger launched the Austrian World Summit,[166] an international climate conference that is held annually in Vienna, Austria. The Austrian World Summit is organized by the Schwarzenegger Climate Initiative and aims is to bring together representatives from politics, civil society and business to create a broad alliance for climate protection and to identify concrete solutions to the climate crisis.

Electoral history

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Arnold Schwarzenegger | 4,206,284 | 48.6 | |

| Democratic | Cruz Bustamante | 2,724,874 | 31.5 | |

| Republican | Tom McClintock | 1,161,287 | 13.5 | |

| Green | Peter Camejo | 242,247 | 2.8 | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Arnold Schwarzenegger (incumbent) | 4,850,157 | 55.9 | |

| Democratic | Phil Angelides | 3,376,732 | 38.9 | |

| Green | Peter Camejo | 205,995 | 2.4 | |

| Libertarian | Art Olivier | 114,329 | 1.3 | |

Presidential ambitions

Presidential aspirations by the Austrian-born Schwarzenegger would be blocked by a constitutional hurdle; Article II, Section I, Clause V, prevents individuals who are not natural-born citizens of the United States from assuming the office. The Equal Opportunity to Govern Amendment in 2003 was widely accredited as the "Amend for Arnold" bill, which would have added an amendment to the U.S. Constitution allowing his run. In 2004, the "Amend for Arnold" campaign was launched, featuring a website and TV advertising promotion.[167][168]

In June 2007, Schwarzenegger was featured on the cover of Time magazine with Michael Bloomberg, and subsequently, the two joked about a presidential ticket together.[169][170]

Business career

Schwarzenegger has also enjoyed a highly successful business career.[24][43] Following his move to the United States, Schwarzenegger became a "prolific goal setter" and would write his objectives at the start of the year on index cards, like starting a mail order business or buying a new car – and succeed in doing so.[37] As a result of his early business and investment success, Schwarzenegger became a millionaire by the age of 25, well before making a name for himself in Hollywood. His path to financial independence came as a result of his success as a proactive businessman and investor involved with a series of lucrative business ventures and real estate investments.[171]

Early ventures

In 1968, Schwarzenegger and fellow bodybuilder Franco Columbu started a bricklaying business. The business flourished thanks to the pair's marketing savvy and an increased demand following the 1971 San Fernando earthquake.[172][173] When signs of profitability emerged as business began to pick up, Schwarzenegger and Columbu rolled over the profits from their bricklaying venture to go on and start their own mail-order business that sold bodybuilding and fitness-related equipment and instructional tapes.[17][172]

Investments

Schwarzenegger transferred profits from the mail-order business and his bodybuilding-competition winnings by rolling the proceeds into his first real estate investment: an apartment building he purchased for $10,000. Schwarzenegger made millions of dollars by investing in a variety of real estate holding companies both within the United States and around the world.[174][175] Schwarzenegger and fellow Hollywood veteran actor and industry adversary Sylvester Stallone brought their long-storied industry rivalry to an end by both investing in the Planet Hollywood[72] chain of international theme restaurants (modeled after the Hard Rock Cafe) along with Bruce Willis and Demi Moore. However, Schwarzenegger severed his financial ties with the chain in early 2000.[176][177] Schwarzenegger remarked that the restaurant did not achieve the success that he had hoped for, claiming he wanted to focus his attention on "new US global business ventures" and his then-burgeoning acting career.[176]

Schwarzenegger also made a private commercial real estate investment in the Easton Town Center, a shopping mall based in Columbus, Ohio.[178] He has talked about some of the mentors who have helped him over the years in business: "I couldn't have learned about business without a parade of teachers guiding me... from Milton Friedman to Donald Trump... and now, Les Wexner and Warren Buffett. I even learned a thing or two from Planet Hollywood, such as when to get out! And I did!"[33] He has significant equity ownership in Dimensional Fund Advisors, an Austin-based investment firm.[179] Schwarzenegger is also the owner of Arnold's Sports Festival, a sports and fitness festival which he started in 1989 and is held annually in Columbus, Ohio. It is a festival that hosts thousands of international health and fitness professionals which has also expanded into a three-day expo. He also owns a film production company called Oak Productions, Inc. and Fitness Publications, a joint book publishing venture partnered with Simon & Schuster.[180]

In 2018, Schwarzenegger partnered with basketball player LeBron James to establish Ladder, a company that developed nutritional supplements to help athletes with severe cramps. The pair sold Ladder to Openfit for an undisclosed amount in 2020 after reporting more than $4 million in sales for that year.[181]

Restaurant

In 1992, Schwarzenegger and his wife opened a restaurant in Santa Monica called Schatzi On Main. Schatzi literally means "little treasure", and colloquially "honey" or "darling" in German. In 1998, he sold his restaurant.[182]

Wealth

In 2024, Forbes estimated that Schwarzenegger was a billionaire.[183]

In June 1997, Schwarzenegger spent $38 million on a private Gulfstream jet.[184]

Regarding his private fortune, Schwarzenegger once quipped: "Money doesn't make you happy. I now have $50 million, but I was just as happy when I had $48 million."[24]

In 2003, Schwarzenegger's net worth was conservatively estimated at $100 million to $200 million.[185]

After separating from his wife, Maria Shriver, in 2011, it was estimated that his net worth had been approximately $400 million, and even as high as $800 million, based on tax returns he filed in 2006.[186]

Commercial advertisements

Schwarzenegger has also appeared in a series of commercials for the Machine Zone game Mobile Strike as a military commander and spokesman.[187]

Personal life

Early relationships

In 1969, Schwarzenegger met Barbara Outland (later Barbara Outland Baker), an English teacher with whom he lived until 1974.[188] The couple first met six to eight months after his arrival in the U.S. Their first date was watching the first Apollo Moon landing on television.[37] They shared an apartment in Santa Monica, California, for three and a half years, and having little money, they would visit the beach all day or have barbecues in the back yard.[37] Although Baker claims that when she first met Schwarzenegger, he had "little understanding of polite society" and she found him a turn-off, she says, "He's as much a self-made man as it's possible to be—he never got encouragement from his parents, his family, his brother. He just had this huge determination to prove himself, and that was very attractive ... I'll go to my grave knowing Arnold loved me."[37] Schwarzenegger said of Baker in his 1977 memoir, "Basically it came down to this: she was a well-balanced woman who wanted an ordinary, solid life, and I was not a well-balanced man, and hated the very idea of ordinary life."[188] Baker has described Schwarzenegger as a "joyful personality, totally charismatic, adventurous, and athletic" but claims that towards the end of the relationship he became "insufferable—classically conceited—the world revolved around him".[189] Baker published her memoir in 2006, Arnold and Me: In the Shadow of the Austrian Oak.[190] Although Baker painted an unflattering portrait of her former lover at times, Schwarzenegger actually contributed to the tell-all book with a foreword, and also met with Baker for three hours.[190] Baker claims that she only learned of his being unfaithful after they split, and talks of a turbulent and passionate love life.[190] Schwarzenegger has made it clear that their respective recollection of events can differ.[190]

Schwarzenegger met his next lover, Beverly Hills hairdresser's assistant Sue Moray, on Venice Beach in July 1977. According to Moray, the couple led an open relationship: "We were faithful when we were both in LA... but when he was out of town, we were free to do whatever we wanted."[25]

Schwarzenegger met television journalist Maria Shriver, niece of President John F. Kennedy, at the Robert F. Kennedy Tennis Tournament in August 1977. He went on to have a relationship with both Moray and Shriver until August 1978 when Moray (who knew of his relationship with Shriver) issued an ultimatum.[25]

Marriage and family

On April 26, 1986, Schwarzenegger married Shriver in Hyannis, Massachusetts.[191] They have four children: Katherine (* 1989), Christina (* 1991), Patrick (* 1993) and Christopher (* 1997).[192][193][194][195] All of their children were born in Los Angeles.[196] The family lived in an 11,000-square-foot (1,000 m2) home in the Brentwood neighborhood of Los Angeles, California,[197][198] with vacation homes in Sun Valley, Idaho, and Hyannis Port, Massachusetts.[199] They attended St. Monica's Catholic Church.[200]

Divorce

On May 9, 2011, Shriver and Schwarzenegger ended their relationship after 25 years of marriage with Shriver moving out of their Brentwood mansion.[201][202][203]

Pursuant to the divorce judgment, Schwarzenegger kept the Brentwood home, while Shriver purchased a new home nearby so that the children could travel between their parents' homes. They shared custody of the two youngest children.[204] Schwarzenegger came under fire after the initial petition did not include spousal support and a reimbursement of attorney's fees.[92] However, he claims this was not intentional and that he signed the initial documents without having properly read them.[92] He filed amended divorce papers remedying this.[92][205] Schwarzenegger and Shriver finalized their divorce in 2021, ten years after separating.[206]

In June 2022, a jury ruled that Maria Shriver was entitled to half of her ex-husband's post-divorce savings that he earned from 1986 to 2011, including a pension.[207]

On May 16, 2011, the Los Angeles Times revealed that Schwarzenegger had fathered a son, Joseph, more than 14 years earlier with an employee in their household, Mildred Patricia "Patty" Baena.[208][209][210] "After leaving the governor's office I told my wife about this event, which occurred over a decade ago," Schwarzenegger said to the Times. In the statement, Schwarzenegger did not mention that he had confessed to his wife only after she had confronted him with the information, which she had done after confirming with the housekeeper what she had suspected about the child.[211] Baena is of Guatemalan origin. She was employed by the family for 20 years and retired in January 2011.[212] The pregnant Baena was working in the home while Shriver was pregnant with the youngest of the couple's four children.[213] Baena's son with Schwarzenegger was born five days after Shriver gave birth.[214][215] Schwarzenegger said that it took seven or eight years before he found out that he had fathered a child with his housekeeper. It was not until the boy "started looking like [him] ... that [he] put things together".[216] Schwarzenegger has taken financial responsibility for the child "from the start and continued to provide support".[217] KNX 1070 radio reported that, in 2010, he bought a new four-bedroom house with a pool for Baena and their son in Bakersfield, California.[218] Baena separated from her husband, Rogelio, a few months after Joseph's birth. She filed for divorce in 2008.[219] Rogelio said that the child's birth certificate was falsified and that he planned to sue Schwarzenegger for engaging in conspiracy to falsify a public document, a serious crime in California.[220]

When asked in January 2014, "Of all the things you are famous for ... which are you least proud of?" Schwarzenegger replied, "I'm least proud of the mistakes I made that caused my family pain and split us up."[221][222][223][224]

Accidents, injuries, and other health problems

Health problems

Schwarzenegger was born with a bicuspid aortic valve, an aortic valve with only two leaflets, where a normal aortic valve has three.[225][226] He opted in 1997 for a replacement heart valve made from his own pulmonary valve, which itself was replaced with a cadaveric pulmonic valve, in a Ross procedure; medical experts predicted he would require pulmonic heart valve replacement surgery within the next two to eight years because his valve would progressively degrade. Schwarzenegger apparently opted against a mechanical valve, the only permanent solution available at the time of his surgery, because it would have sharply limited his physical activity and capacity to exercise.[227]

On March 29, 2018, Schwarzenegger underwent emergency open-heart surgery for replacement of his replacement pulmonic valve.[228] He said about his recovery: "I underwent open-heart surgery this spring, I had to use a walker. I had to do breathing exercises five times a day to retrain my lungs. I was frustrated and angry, and in my worst moments, I couldn't see the way back to my old self."[229]

In 2020, 23 years after his first surgery, Schwarzenegger underwent a surgery for a new aortic valve.[230]

Accidents and injuries

On December 9, 2001, he broke six ribs and was hospitalized for four days after a motorcycle crash in Los Angeles.[231]

Schwarzenegger saved a drowning man in 2004 while on vacation in Hawaii by swimming out and bringing him back to shore.[232]

On January 8, 2006, while Schwarzenegger was riding his Harley-Davidson motorcycle in Los Angeles with his son Patrick in the sidecar, another driver backed into the street he was riding on, causing him and his son to collide with the car at a low speed. While his son and the other driver were unharmed, Schwarzenegger sustained an injury to his lip requiring 15 stitches. "No citations were issued," said Officer Jason Lee, a Los Angeles Police Department spokesman.[233] Schwarzenegger did not obtain his motorcycle license until July 3, 2006.[234]

Schwarzenegger tripped over his ski pole and broke his right femur while skiing in Sun Valley, Idaho, with his family on December 23, 2006.[235] On December 26, he underwent a 90-minute operation in which cables and screws were used to wire the broken bone back together. He was released from St. Johns Hospital and Health Center on December 30, 2006.[236]

Schwarzenegger's private jet made an emergency landing at Van Nuys Airport on June 19, 2009, after the pilot reported smoke coming from the cockpit, according to a statement released by his press secretary. No one was harmed in the incident.[237]

On May 18, 2019, while on a visit to South Africa, Schwarzenegger was attacked and dropkicked from behind by an unknown malefactor while giving autographs to his fans at one of the local schools. Despite the surprise and unprovoked nature of the attack, he reportedly suffered no injuries and continued to interact with fans. The attacker was apprehended and Schwarzenegger declined to press charges against him.[238][239][240]

Schwarzenegger was involved in a multi-vehicle collision on the afternoon of Friday, January 21, 2022. Schwarzenegger was driving a black GMC Yukon SUV near the intersections of Sunset Boulevard and Allenford Avenue in the Brentwood neighborhood of Los Angeles, when his vehicle collided with a red Toyota Prius. The driver of the Prius was transported to the hospital for injuries sustained to her head. Schwarzenegger was uninjured.[241][242][243]

Height

Schwarzenegger's official height of 6 ft 2 in (1.88 m) has been brought into question by several articles. During his bodybuilding days in the late 1960s, it was claimed that he measured 6 ft 1.5 in (1.867 m). However, in 1988, both the Daily Mail and Time Out magazine mentioned that Schwarzenegger appeared noticeably shorter.[244] Prior to running for governor, Schwarzenegger's height was once again questioned in an article by the Chicago Reader.[245] As governor, Schwarzenegger engaged in a light-hearted exchange with Assemblyman Herb Wesson over their heights. At one point, Wesson made an unsuccessful attempt to, in his own words, "settle this once and for all and find out how tall he is" by using a tailor's tape measure on the Governor.[246] Schwarzenegger retaliated by placing a pillow stitched with the words "Need a lift?" on the five-foot-five-inch (1.65 m) Wesson's chair before a negotiating session in his office.[247] Democrat Bob Mulholland also claimed Schwarzenegger was 5 ft 10 in (1.78 m) and that he wore risers in his boots.[248] In 1999, Men's Health magazine stated his height was 5 ft 10 in (1.78 m).[249]

Autobiography

Schwarzenegger's autobiography, Total Recall, was released in October 2012. He devotes one chapter called "The Secret" to his extramarital affair. The majority of his book is about his successes in the three major chapters in his life: bodybuilder, actor, and Governor of California.[250] Schwarzenegger released a second book in 2023 titled Be Useful: Seven Tools for Life, which features life advice and again touches on his life experiences.

Vehicles

Growing up during Allied-occupied Austria, Schwarzenegger commonly saw heavy military vehicles such as tanks as a child.[251] As a result, he paid $20,000 to bring his Austrian Army M47 Patton tank (331) to the United States,[252] which he previously operated during his mandatory service in 1965. However, he later obtained his vehicle in 1991/2,[253] during his tenure as the Chairmen of the President's Council on Sports, Fitness, and Nutrition,[254] and now uses it to support his charity.[253] His first car ever was an Opel Kadett in 1969 after serving in the Austrian army, then he rode a Harley-Davidson Fat Boy in 1991.[255]

Moreover, he came to develop an interest in large vehicles and became the first civilian in the U.S. to purchase a Humvee. He was so enamored by the vehicle that he lobbied the Humvee's manufacturer, AM General, to produce a street-legal, civilian version, which they did in 1992; the first two Hummer H1s they sold were also purchased by Schwarzenegger. In 2010, he had one regular and three running on non-fossil power sources; one for hydrogen, one for vegetable oil, and one for biodiesel.[256] Schwarzenegger was in the news in 2014 for buying a rare Bugatti Veyron Grand Sport Vitesse. He was spotted and filmed in 2015 in his car, painted silver with bright aluminium forged wheels. His Bugatti has its interior adorned in dark brown leather.[257] In 2017, Schwarzenegger acquired a Mercedes G-Class modified for all-electric drive.[258]

The Hummers that Schwarzenegger bought in 1992 are so large—each weighs 6,300 lb (2,900 kg) and is 7 feet (2.1 m) wide—that they are classified as large trucks, and U.S. fuel economy regulations do not apply to them. During the gubernatorial recall campaign, he announced that he would convert one of his Hummers to burn hydrogen. The conversion was reported to have cost about $21,000. After the election, he signed an executive order to jump-start the building of hydrogen refueling plants called the California Hydrogen Highway Network, and gained a United States Department of Energy grant to help pay for its projected US$91,000,000 cost.[259] California took delivery of the first H2H (Hydrogen Hummer) in October 2004.[260]

Public image and legacy

Schwarzenegger has been involved with the Special Olympics for many years after they were founded in 1968 by his later mother-in-law Eunice Kennedy Shriver.[261] In 2007, Schwarzenegger was the official spokesperson for the Special Olympics held in Shanghai, China.[262] Schwarzenegger believes that quality school opportunities should be made available to children who might not normally be able to access them.[263] In 1995, he founded the Inner City Games Foundation (ICG) which provides cultural, educational and community enrichment programming to youth. ICG is active in 15 cities around the country and serves over 250,000 children in over 400 schools countrywide.[263] He has also been involved with After-School All-Stars and founded the Los Angeles branch in 2002.[264] ASAS is an after school program provider, educating youth about health, fitness and nutrition.

On February 12, 2010, Schwarzenegger took part in the Vancouver Olympic Torch relay. He handed off the flame to the next runner, Sebastian Coe.[265]

Schwarzenegger had a collection of Marxist busts, which he requested from Russian friends during the dissolution of the Soviet Union, as they were being destroyed. In 2011, he revealed that his wife had requested their removal, but he kept the one of Vladimir Lenin present, since "he was the first".[266] In 2015, he said he kept the Lenin bust to "show losers."[267]

Schwarzenegger is a supporter of Israel, and has participated in a Los Angeles pro-Israel rally[268] among other similar events.[269] In 2004, Schwarzenegger visited Israel to break ground on Simon Wiesenthal Center's Museum of Tolerance Jerusalem, and to lay a wreath at the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial, he also met with Prime Minister Ariel Sharon and President Moshe Katsav.[270] In 2011, at the Independence Day celebration hosted by the Israeli Consulate General in Los Angeles, Schwarzenegger said: "I love Israel. When I became governor, Israel was the first country that I visited. When I had the chance to sign a bill calling on California pension funds to divest their money from companies that do business with Iran, I immediately signed that bill", then he added, "I knew that we could not send money to these crazy dictators who hate us and threaten Israel any time they have a bad day."[269]