Prime Minister of Spain

| Prime Minister of Spain | |

|---|---|

| Presidente del Gobierno de España | |

| |

since 2 June 2018 | |

| Government of Spain Office of the Prime Minister | |

| Style | The Most Excellent |

| Type | Head of government |

| Member of | |

| Reports to | Monarch Cortes Generales |

| Residence | Palace of Moncloa |

| Seat | Madrid, Spain |

| Nominator | The Congress of Deputies |

| Appointer | The Monarch |

| Term length | No fixed term |

| Deputy | Deputy Prime Minister |

| Salary | €90,000 per annum[1] |

| Website | lamoncloa |

|

|---|

The prime minister of Spain, officially president of the Government[2] (Spanish: Presidente del Gobierno), is the head of government of Spain. The prime minister nominates the ministers and chairs the Council of Ministers. In this sense, the prime minister establishes the Government policies and coordinates the actions of the Cabinet members. As chief executive, the prime minister also advises the monarch on the exercise of their royal prerogatives.

Although it is not possible to determine when the position actually originated, the office of prime minister has evolved throughout history to what it is today. The role of prime minister (then called Secretary of State) as president of the Council of Ministers, first appears in a royal decree of 1824 by King Ferdinand VII.[3] The current office was established during the reign of Juan Carlos I, in the 1978 Constitution, which describes the prime minister's constitutional role and powers, how the prime minister accedes to, and is removed from office, and the relationship between the prime minister and Parliament.

Upon a vacancy, the monarch nominates a candidate for a vote of confidence by the Congress of Deputies, the lower house of the Cortes Generales. The process is a parliamentary investiture by which the head of government is elected by the Congress of Deputies. In practice, the prime minister is almost always the leader of the largest party in the Congress, although not necessarily. The prime minister's official residence and office is Moncloa Palace in Madrid.[4]

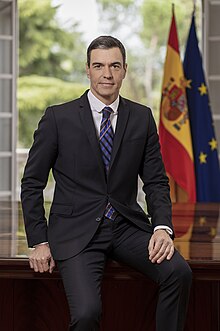

Pedro Sánchez, of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE), has been prime minister since 2 June 2018. He first came to power after a successful motion of no confidence against former prime minister Mariano Rajoy.[5] Since then, Sánchez has led three governments, the most—along with Adolfo Suárez—just behind fellow socialist Felipe González, prime minister from 1982 to 1996.[6] King Felipe VI re-appointed Sánchez for the third time on 17 November 2023[7] after he reached a coalition agreement with Sumar and gathered the support of other minor parties.[8] His third government took office on 21 November 2023.[9]

Official title

[edit]The Spanish head of government has been known, since 1939, as "President of the Government" (Spanish: Presidente del Gobierno).[10]

Not only is this term confusing for English speakers because Spain is not a republic, but because the parliamentary speakers are also referred to as presidents of their respective chambers. For example, both President George W. Bush and his brother, Florida governor Jeb Bush, referred to José María Aznar as "president" on separate occasions,[11][12] and Donald Trump referred to Mariano Rajoy both as "President" and "Mr. President" during Rajoy's 2017 White House visit.[13] While this term of address was not incorrect, it could be misleading to English speakers so prime minister is commonly used as a culturally equivalent term to ensure clarity.

Use of the term "president" dates back to 1834 and the regency of Maria Christina when, styled after the head of government of the French July Monarchy (1830), the official title was the "President of the Council of Ministers" (Presidente del Consejo de Ministros). This remained until 1939, when the Second Spanish Republic ended. Before 1834 the figure was known as "Secretary of State" (Secretario de Estado), a denomination used today for junior ministers.

Spain was not unique in this regard: it was one of several European parliamentary systems, including France, Italy and the Irish Free State, that styled the head of government as 'presidents' of the government rather than the Westminster term of 'prime minister' (see President of the Council for the full list of corresponding terms). However the term 'president' is far older.

Origin

[edit]Since the 15th century, the Spanish monarchs has delegated its executive powers in relevant personalities. Two are the most important: the validos and the secretaries of state. The validos, which existed since early 15th century to the late 17th century were people of the highest confidence of the monarchs and they exercised the Crown's power in the monarch's name.[14] Since the 18th century, the validos disappeared and the secretaries of state were introduced. Both positions were de facto prime ministers (as demonstrated by the fact that since the tenure of the count-duke of Olivares, valido of Felipe IV, the validos were often called by courtiers and authors already in the 17th century as "principal minister or prime minister of Spain"[14]) although they can not be completely compared.

On 19 November 1823, after a brief liberal democratic period called the Liberal Triennium between 1820 and 1823, King Ferdinand VII re-established the absolute monarchy and created the Council of Ministers that continues to exist today.[15] This council, when not chaired by the monarch, was chaired by the secretary of state for foreign affairs (Spanish: Secretario de Estado y del Despacho de Estado), who acted as prime minister.[15] This role was ratified by the Royal Statute of 1834, which constitutionalized for the first time the figure of the prime minister under the name of "President of the Council of Ministers", invested with executive powers.

During the 19th century, the position changed names frequently. After the Glorious Revolution of 1868, it was renamed President of the Provisional Revolutionary Joint and later President of the Provisional Government. In 1869, the office resumed the name of President of the Council of Ministers. Following the abdication of King Amadeus I, during the First Republic (1873–1874) the office was known as the President of the Executive Power and was also head of state. In 1874, the office name reverted to President of the Council of Ministers.

Since its inception, the prime minister has been appointed and dismissed by the will of the monarch. Successive constitutions have confirmed this royal prerogative of the monarch in the Constitution of 1837 (article 47),[16] article 46 of the Constitution of 1845,[17] the Constitution of 1869 (article 68),[18] and the Constitution of 1876 (article 54).[19]

With the fall of the First Republic and the restoration of the Bourbon dynasty on King Alfonso XII, the office maintained its original name until the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera, when it was renamed to President of the Military Directory. In 1925, the original name was restored again.

The Republican Constitution of 1931 provided for the prime minister and the rest of the government to be appointed and dismissed by the President of the Republic but they were responsible before the Parliament and the Parliament could vote to dismiss the prime minister or a minister even against the will of the president of the republic.[20] In the Civil War, the head of government among the Nationalists was called Chief of the Government of the State and since January 1938 the office acquired the current name, President of the Government, but between that date and 1973 the office was held by Francisco Franco as dictator of Spain.

In 1973, Francisco Franco separated the head of state from the head of government, and that division still exists today, with the prime minister democratically elected by the Parliament which is itself elected by universal suffrage, free and equal. Adolfo Suárez was the first democratically elected prime minister of the post-Franco government. He was originally appointed by King Juan Carlos I on 3 July 1976, and he was confirmed in the office by popular vote after the 1977 Spanish general election.[21]

Royal nomination and congressional confirmation

[edit]Once a general election has been called by the monarch, political parties designate their candidates to stand for prime minister—usually the party leader. A prime minister is dismissed from office the day after the election, but remains in office as a caretaker until his/her successor is sworn in.

Following the general election and other circumstances provided for in the Constitution, the sovereign meets with the leaders of the parties represented in the Congress of Deputies, and then consults with the Speaker of the Congress of Deputies (Spanish: Presidente de Congreso de los Diputados) as representative of the whole of parliament), before nominating a candidate for the prime ministership. This process is spelled out in Section 99 of the Constitution.[22]

By political custom established by Juan Carlos I since the ratification of the 1978 Constitution, the sovereign's nominees have usually been from parties who have a plurality of seats in the Congress (i.e. the largest party). Although there is no legal requirement for this, it is seen as a royal endorsement of the democratic process—a fundamental concept enshrined in the 1978 Constitution. The largest party can end up not ruling if rival parties form a coalition—as happened in 2018 with the election of PSOE leader Pedro Sánchez. More commonly, if neither of the two major parties (Spanish Socialist Workers' Party is able to command an absolute majority of the Congress by themselves, one will rule as a minority by adopting some aspects of the minor party platforms in an effort to attract them into parliamentary agreements to vote in the major party's favour, or at least abstain.

The monarch's order nominating a prime ministerial candidate is countersigned by the Speaker of the Congress, who then presents the nominee before the Congress of Deputies in a process known as a parliamentary investiture (Investidura parlamentaria). During the investiture proceedings, the candidate describes their political agenda in an Investiture Speech to be debated and submitted for a vote of confidence (Cuestión de confianza) by the Congress, effecting an indirect election of the head of government.[22][23]

Confidence is awarded if the candidate receives a majority of votes in the first poll (currently 176 out of 350 MPs), but if the confidence is not granted, a second vote is scheduled forty-eight hours later in which a simple majority of votes cast (i.e., more "yes" than "no" votes) is required.[22] Following the second vote, if confidence by the Congress is still not reached, then the monarch again meets with political leaders and the Speaker, and submits a new nominee for a vote of confidence (exceptionally, in 2016 King Felipe VI opted for not nominating more candidates and call for new elections[24]).[22] If, within two months, no candidate has won the confidence of the Congress then the monarch dissolves the Cortes and calls for a new general election.[22] The monarch's royal decree is countersigned by the Speaker of the Congress.[22]

Oath of office

[edit]

After the nominee is confirmed, the Speaker of the Congress formally reports the fact to the sovereign. The monarch then appoints the candidate as the new prime minister and this too is countersigned by the Speaker.[22]

During the swearing-in ceremony presided over by the monarch, customarily at the Audience Hall of the Royal Palace of Zarzuela, the prime minister–designate takes an oath of office over an open Constitution and—at choice since 2014[26]—next to a Bible and a crucifix. The prime minister must take the oath or affirmation placing the right hand on the Constitution. Currently, only one prime minister has refused to take the oath of office next to religious symbols: Pedro Sánchez, along with most of his Cabinet members.[27] His predecessor, Mariano Rajoy, a Catholic, put his right hand on the Constitution and, at the same time, his left hand on the Bible.[28] As per tradition, if the members of the government choose not to take the oath along with any religious symbols, they use the word "prometo" ("I promise"), whereas if the take the oath with the Bible, they use the word "juro" ("I swear"). The oath as taken by Prime Minister Zapatero on his first term in office on 17 April 2004 was:[25]

Juro/Prometo, por mi conciencia y honor, cumplir fielmente las obligaciones del cargo de Presidente del Gobierno con lealtad al Rey, guardar y hacer guardar la Constitución como norma fundamental del Estado, así como mantener el secreto de las deliberaciones del Consejo de Ministros.

I swear/promise, under my conscience and honor, to faithfully execute the duties of the office of Prime Minister with loyalty to the King, obey and enforce the Constitution as the main law of the State, and preserve in secret the deliberations of the Council of Ministers.

Once appointed, the prime minister forms his government whose ministers are appointed and removed by the monarch on the prime minister's advice. In the political life of Spain, the monarch would already be familiar with the various political leaders in a professional capacity, and perhaps less formally in a more social capacity, facilitating their meeting following a general election. Conversely, nominating the party leader whose party maintains a plurality and who are already familiar with their party manifesto facilitates a smoother nomination process. In the event of coalitions, the political leaders would customarily have met beforehand to hammer out a coalition agreement before their meeting with the Sovereign.

Constitutional authority

[edit]Title IV of the Constitution defines the Government and its responsibilities.[22] The Government consists of the prime minister and the ministers. The government conducts domestic and foreign policy, civil and military administration, and the defense of the nation all in the name of the monarch on behalf of the people. Additionally, the government exercises executive authority and statutory regulations.[22] The main collective decision-making body of the Government is the Council of Ministers, chaired by the prime minister and, after a formal request by the Prime Minister, by the monarch.

There is no provision in the Spanish Constitution for explicitly granting any emergency powers to the government. However, Section 56 of the Constitution vests the monarch as the "arbitrator and moderator of the institutions" of government, [The King] arbitrates and moderates the regular functioning of the institutions (arbitra y modera el funcionamiento regular de las instituciones).[29][30] This provision could be understood as allowing the monarch or his government ministers to exercise emergency authority in times of national crisis, such as when the monarch used his authority to back the government of the day and call for the military to abandon the 23-F coup attempt in 1981.[31][32]

The prime minister also assumes political responsibility for most acts of the sovereign. While the monarch is vested with executive power, his acts are not valid unless countersigned by a minister. Under Article 64 of the Constitution, that minister—usually the prime minister—assumes political responsibility for the act in question. In these sense, the Constitution grants the prime minister the initiative to request the monarch for calling a referendum, for calling for new elections or for dissolving any of the legislative chambers. In Spain, the government ministers cannot force the prime minister resignation and this idea is reinforced when the Constitution grants the prime minister the sole initiative to request the Congress for a vote of confidence. In constitutional matters, the primacy of the prime minister over the ministers is also evident, since the prime ministers alone is responsible for the government initiative to challenge the constitutionality of a law.

Office of the Prime Minister

[edit]

The Office of the Prime Minister (Spanish: Presidencia del Gobierno, lit. 'Presidency of the Government') is the combination of government departments and services that are at the service of the Prime Minister to fulfill its constitutional duties.[33] It was established around 1834 when officials and budget began to be assigned to the personal Secretariat of the Prime Minister. Today, it acts as a ministerial department, although it is not formally one of them, and approximately 2,000 people work there.[34]

The Prime Minister's Office principal departments are:[35]

- The Ministry of the Presidency.

- The Secretariat of State for Relations with the Cortes and Constitutional Affairs.

- The Secretariat of State for Democratic Memory.

- The Cabinet Office, headed by the Moncloa Chief of Staff.

- The General Secretariat of the Presidency of the Government.

- The Department of National Security.

- The Office for Economic Affairs and G20, with the rank of secretariat of state.

- The Secretariat of State for Press.

The autonomous agency Patrimonio Nacional, which manages Crown properties, depends on this Office through the Ministry of the Presidency.[36]

Security and transport

[edit]

The Cabinet Office, through the General Secretariat of the Presidency of the Government, is responsible for the protocol and security affairs.[35] Within the General Secretariat, there is a Department of Security of the Presidency of the Government (DSPG) that coordinates the efforts of the National Police Corps and the Civil Guard in the protection of the Prime Minister and his family, as well as the infraestructure and personnel of the Moncloa Government Complex.[35]

The vehicles used by the Prime Minister are provided by the State Vehicle Fleet (PME), an autonomous agency of the Ministry of Finance that provides the government with all type of vehicles and well-trained drivers. The air transportation of the Prime Minister and other government officials is mainly provided by the 45th Air Force Group (planes) and the 402nd Air Force Squadron (helicopters).

Resignation and dissolution of Parliament

[edit]The Parliament, and thus, the Government, sit for a term no longer than four years. Before that date, the prime minister may offer his resignation to the sovereign. If the Prime Minister does so while advising the monarch to dissolve parliament, the sovereign will call for a snap election, but no sooner than a year after the prior general election.[37]

If a prime minister resigns without advising the monarch to call for new elections, dies or becomes incapacitated while in office, then the government as a whole resigns and the process of royal nomination and appointment takes place. The deputy prime minister, or in the absence of such office, the first minister by precedence, would then take over the day-to-day operations in the meantime as acting-prime minister, even while the deputy prime minister themselves may be nominated by the monarch and stand for a vote of confidence. Also, if at the conclusion of the four years, the prime minister has not asked for its dissolution, according to Title II Section 56, the monarch must dissolve the Parliament and call for a new general election.[38]

Although the prime minister's position is strengthened by constitutional limits on the Congress' right to withdraw confidence from the government, the Cortes Generales has two ways of forcing the prime minister's resignation: passing a motion of no confidence or rejecting a motion of confidence. In the first case, and following the German model, a prime minister can only be removed by a constructive vote of no confidence. While the Congress can censure the government at any time, the censure motion must also include the name of a prospective replacement for the incumbent prime minister. If the censure motion is successful, the replacement candidate is automatically deemed to have the confidence of the Congress, and the monarch is required to appoint them as the new prime minister. As of 2023, only Pedro Sánchez managed to remove a sitting prime minister with a vote of no confidence in 2018, making him prime minister.[39][40] In the second case, the prime minister, after deliberation by the Council of Ministers, can propose a vote of confidence regarding the government's policies in Congress. If Congress does not give the prime minister its confidence, the prime minister must resign. As of 2023, only prime minister Adolfo Suárez in 1980 and Felipe González in 1990 proposed a vote of confidence, both successfully.[41]

Precedence, privileges and form of address

[edit]

The Prime Minister is the second authority of the Kingdom of Spain, outranking all other State authorities except members of the royal family.[42]

In 2023, the Prime Minister received a salary of €90,010[43] and additional €13,422 as member of parliament.[44] With this salary, the prime minister is not the highest paid official of Spain, being surpassed by other State authorities such as the royal family[45] (the King, €269,296; the Queen, €148,105; and the Queen Mother, €121,186), the president of the Congress of Deputies (€230,931),[46] the president of the Constitutional Court (€167,169),[43] the president of the Supreme Court (€151,186)[43] and the president of the Court of Auditors (€130,772),[43] among others.

The prime minister is constitutionally protected against ordinary prosecution. Although the Prime Minister does not have legal immunity like the monarch, the prime minister, as well as the members of the Royal Family, the Government, the Congress of Deputies and the Senate, can only be criminally responsible before the Criminal Chamber of the Supreme Court (Spanish Constitution, Part IV § 102).

Although it is not formally regulated, Spanish custom establishes that the prime minister receives the treatment of The Most Excellent (Spanish: Excelentísimo Señor, f. Excelentísima Señora). This treatment has been customary for the government ministers since, at least, the 18th century, and in the case of the prime minister, this treatment is reinforced as member of the Order of Charles III, whose article 13 states that "the Knights and the Dames of the Collar, as well as the Knights and Dames Grand Cross, will receive the treatment of Most Excellent Lord and Most Excellent Lady".[47]

Deputy

[edit]

The Spanish Constitution foresee the office of deputy prime minister and also the possibility of having more than one deputy prime minister. Although the position of deputy prime minister has existed intermittently since 1840, the Constitution endorses what was established in the Organic Act of the State of 1967,[48] which provided for the first time the possibility of appointing more than one deputy and, in 1974, this provision became effective when Prime Minister Carlos Arias Navarro appointed three deputies (José García Hernández, Antonio Barrera de Irimo and Licinio de la Fuente).[49] Since then, three more prime ministers (Adolfo Suárez, José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero and Pedro Sánchez) have had more than one deputy.[50] The second government of Pedro Sánchez holds the record for most deputies, appointing four.[51][50] This large number of deputy prime ministerships was interpreted as a maneuver to reduce the political weight of his second deputy prime minister and leader of the minority party in the coalition, Pablo Iglesias Turrión.[52][53][54]

Succession

[edit]According to article 101 of the Spanish Constitution, the prime minister and its government only ceases in the cases of resignation, a failed motion of confidence, a motion of no confidence against the prime minister or the death of the prime minister. In the first three options, there is no succession, because the prime minister remains as caretaker prime minister until a new prime minister is elected by the Congress of Deputies.

If the Prime Minister dies, the 1997 Government Act provides that the Prime Minister be succeeded by the Deputy Prime Minister and, if there is more than one, by the Deputy Prime Ministers, depending on their order. If there is no deputy prime minister, the Government Act establishes that the prime minister will be replaced by the ministers, according to the order of precedence of the Departments. This means that the first in the line of succession after the deputy prime ministers would be the Minister of Foreign Affairs, followed by the Minister of Justice, the Minister of Defense and the Minister of Finance. These four ministers are the first and great offices created in 1714 by King Philip V.[55]

Order of Charles III

[edit]

The Order of Charles III, officially the Royal and Distinguished Spanish Order of Charles III, was established in 1771 by King Charles III and is today the country's highest civil honor. The current regulation of the order, established in October 2002, states that the prime minister is the Grand Chancellor of the Order (second to the Grand Master, the Monarch).[47]

Upon taking office, the new prime minister shall be invested with the degree of Knight or Dame Grand Cross of the Order and with this rank he will act as Grand Chancellor of the same.[47] It is responsibility of the Grand Chancellor to submit to the approval of the Council of Ministers Royal Decrees granting the degrees of Collar and Grand Cross, and all titles of the different degrees of the Royal Order must bear his signature and the monarch's.[47]

The last person to join the order was Sergio Mattarella, President of the Italian Republic, who was awarded the collar of the order in December 2024 on the occasion of the State visit of the Spanish monarchs to Italy.[56]

Retirement honours and privileges

[edit]Upon retirement, it is customary for the monarch to grant a prime minister some honour or dignity. The honour bestowed is commonly the Collar of the Order of Isabella the Catholic, the second highest civil honor, while the ministers receive the Grand Cross of the Order of Charles III (the highest civil distinction).[57][58] This is because the prime minister is, since he is appointed as such by the sovereign, a Knight or Dame Grand Cross of the Order of Charles III, for which he is awarded the next highest distinction.

In addition to these honors, the monarch might offer the former prime minister a peerage,[59] being the highest marks of distinction that he may bestow in his capacity as the fons honorum in Spain. Conventionally, the Title of Concession creating the dignity must be countersigned by a government minister. When a title is created for a former prime minister, the succeeding prime minister customarily countersigns the royal decree.

Although prior to the reign of Alfonso XIII many noble titles were granted —or the rank of those who already possessed it one was raised— to prime ministers and ministers (such as the Dukedom of Prim —granted to the daughter of late prime minister Juan Prim— or the Dukedom of Castillejos —awarded to the other son of the aforementioned prime minister—), it was not until this historical period when it became customary, since King Alfonso XIII granted a total of sixteen of these dignities to former prime ministers or their relatives during his reign.[60] Of these, four were dukedoms (granted to relatives of assassinated prime ministers), three were marquessates and two counties, as well as seven grandships were granted.[60] Likewise, the monarch also rewarded with numerous golden fleeces.[60] King Juan Carlos I wanted to restore this tradition and, therefore, as a reward for their service, the last noble titles granted (both with grandship) were those of Adolfo Suárez (to whom the golden fleece was also awarded in 2007[61]), who was created Duke of Suárez in 1981[62] and Leopoldo Calvo-Sotelo, created Marquess of the Ría de Ribadeo in 2002, twenty years after holding the office.[63] The last prime minister to be offered a noble title was Felipe González, who rejected the offer.[64] Since then, neither King Juan Carlos I nor King Felipe VI have offered prime ministers such an honor.

Staff, salary and office

[edit]In 1983, the first government of Felipe González established the "Statute of Former Prime Ministers", which granted retired prime ministers, for four years, the right to have an office composed by two civil servants, a minimum endowment of 2.5 million pesetas each year for office expenses and an official vehicle with driver.[65]

Nine years later, the government updated the Statute, removing the time limit the prime minister would receive privileges, including diplomatic assistance abroad, security, a personal salary for two years after leaving the office and, free pass in public transportation and an undetermined endowment for office expenses.[66]

Since 2004, the retired prime ministers are eligible for a seat in the Council of State for life.[67] As of 2023, only Jose María Aznar (2005–2006) and José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero (2011–2015) used this privilege.[68]

For the fiscal year 2023, each of the living prime ministers receive €74,580 for the sustenance of their respective offices.[69]

Recent prime ministers

[edit]Timeline

[edit]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Carlos Molina (7 October 2022). "Pedro Sánchez ganará 90.010 euros, 5.410 euros más que las tres vicepresidentas". El País (in Spanish). Prisa. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ "La Moncloa. Pedro Sánchez Pérez-Castejón, President of the Government of Spain [President/Biography]".

- ^ Escudero López, José Antonio (1972). "The creation of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers". History of Spanish Law Yearbook (in Spanish). XLII: 757–767.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Rodríguez, Jesús (20 April 2018). "Moncloa Confidential: A peek inside the Spanish PM's seat of power". EL PAÍS English. Retrieved 3 December 2023.

- ^ Jones, Sam (2 June 2018). "Pedro Sánchez sworn in as Spain's prime minister after no-confidence vote". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 3 December 2023.

- ^ 20minutos (18 November 2023). "Tres investiduras, dos elecciones ganadas, dos mociones... las cifras de un Sánchez que ya amenaza los récords de Felipe González". www.20minutos.es - Últimas Noticias (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 December 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ R, J. A. (17 November 2023). "Pedro Sánchez promete ante el Rey su tercer mandato como presidente del Gobierno". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 December 2023.

- ^ "Spain's parliament confirms Pedro Sánchez as prime minister". POLITICO. 16 November 2023. Retrieved 3 December 2023.

- ^ CABALLERO, ÁLVARO (21 November 2023). "El Gobierno echa a andar con la toma de posesión de los ministros". RTVE.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 December 2023.

- ^ Lea, C. (2001). The Oxford Spanish Dictionary and Grammar (2nd ed.).

- ^ Office of the Press Secretary (12 June 2001). "Joint Press Conference with President George W. Bush and President Jose Maria Aznar". The White House. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- ^ "Jeb Bush agradece el apoyo "del presidente de la República española"" [Jeb Bush thanks the "President of the Spanish Republic" for his support]. El País (in Spanish). Madrid: Prisa. 18 February 2003. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ^ Gallucci, Nicole (26 September 2017). "Trump repeatedly called the prime minister of Spain 'president,' and everyone is confused". Mashable. Ziff Davis, LLC. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- ^ a b Escudero López, José Antonio (2009). Privados, validos y primeros ministros en la monarquía española de Antiguo Régimen (in Spanish) (39th ed.). Madrid: Anales de la Real Academia de Jurisprudencia y Legislación. pp. 321–331. ISBN 978-84-9849-817-2.

- ^ a b Fontana, Josep (1973). Treasury and State, 1823-1833 (in Spanish). Madrid: Institute of Fiscal Studies. p. 88. ISBN 9788480080842.

- ^ "Constitución española de 1837". es.wikisource.org (in Spanish). Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ^ "Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy of 1845" (PDF) (in Spanish). 1845.

- ^ "Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy of 1869" (PDF) (in Spanish). 1869.

- ^ "Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy of 1876" (in Spanish). 1876.

- ^ "Spanish Constitution of 1931". scribd. Retrieved 5 June 2024.

- ^ "Spain's Election Victor". The New York Times. 17 June 1977. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Spanish Constitution, 1978, Part IV Government and Administration

- ^ Speech by Zapatero at the session for his investiture as Prime Minister

- ^ Alberola, Miquel (27 April 2016). "El Rey no propone a ningún candidato y aboca a nuevas elecciones en junio". El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ a b (in Spanish) Video: Rodríguez Zapatero is sworn into his second term (RTVE's Canal 24H, 12 April 2008)

- ^ EFE; País, El (9 July 2014). "Felipe VI cambia el protocolo y permite la jura del cargo sin Biblia ni crucifijo". El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ "Pedro Sánchez, presidente aconfesional: Promete su cargo ante el Rey sin Biblia ni crucifijo". 2 June 2018.

- ^ DÍAS, CINCO (31 October 2016). "Rajoy jura el cargo de presidente ante Felipe VI". Cinco Días (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ Spanish Constitution, 1978, Part II The Crown

- ^ The Royal Household of H.M. The King website

- ^ "Sinopsis artículo 62 - Constitución Española". app.congreso.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- ^ Polo, Raquel Pérez (22 February 2021). "Don Juan Carlos, la historia detrás del hombre que paró el golpe del 23-F". COPE (in Spanish). Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- ^ Spanish Royal Academy. "Definición de Presidencia del Gobierno - Diccionario panhispánico del español jurídico - RAE". www.dpej.rae.es (in Spanish). Pan-Hispanic Spanish Law Dictionary. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ "Los funcionarios de La Moncloa exigen por escrito al Gobierno la cifra de contagios por Covid-19 en el complejo presidencial". Vozpópuli (in Spanish). 3 April 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ a b c Office of the Prime Minister (1 August 2022), Real Decreto 662/2022, de 29 de julio, por el que se reestructura la Presidencia del Gobierno (in Spanish), pp. 110312–110323, retrieved 19 November 2023

- ^ "Real Decreto 373/2020, de 18 de febrero, por el que se desarrolla la estructura orgánica básica del Ministerio de la Presidencia, Relaciones con las Cortes y Memoria Democrática". www.boe.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ Snap elections have been used only threes since the 1978 Constitution was ratified, ex-PM Felipe González invoked his constitutional right to dissolve the Cortes three times in 1989, 1993, and 1996

- ^ Title II Section 56 the monarch is the "arbitrator and moderator of the regular functioning of the institutions"

- ^ Maestro, Laura Smith-Spark,Laura Perez (1 June 2018). "Rajoy forced out as Spain's Prime Minister in confidence vote". CNN. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Mariano Rajoy: Spanish PM forced out of office". BBC News. 1 June 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ "Así fueron las cuestiones de confianza y mociones de censura de la Democracia | España | elmundo.es". www.elmundo.es. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ Office of the Prime Minister. "General Order of Precedence in the State". www.boe.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ a b c d Hidalgo, Emilio Sánchez (6 October 2022). "Así son los sueldos de los altos cargos: 167.000 euros para el presidente del Constitucional y 90.000 para el del Gobierno". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ Torres, Lola Gutiérrez / Carla (17 November 2023). "¿Cuánto ganará Pedro Sánchez como presidente del Gobierno?". elperiodico (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ AGENCIAS, RTVE es / (15 February 2023). "Felipe VI cobrará este año 269.296 euros". RTVE.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ lainformacion.com (3 October 2022). "Cuánto cobrarán los diputados tras la subida del 3,5% de sus sueldos en 2023". La Información (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ a b c d Office of the Prime Minister (12 October 2002). "Real Decreto 1051/2002, de 11 de octubre, por el que se aprueba el Reglamento de la Real y Distinguida Orden Española de Carlos III". www.boe.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ Office of the Head of State. "Ley Orgánica del Estado, número 1/1967, de 10 de enero". www.boe.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ "Gabinete Arias Navarro". El País (in Spanish). 2 July 1976. ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ a b "Sánchez encabezará el gobierno de la democracia con más vicepresidencias". Europa Press. 9 January 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ GUTIÉRREZ, JAIME (13 January 2020). "El Gobierno de Pedro Sánchez será el segundo más numeroso de la democracia con 23 miembros". RTVE.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ Sierra, Iolanda Mármol,Juan Ruiz (9 January 2020). "Sánchez resta peso a Iglesias al crear cuatro vicepresidencias". elperiodico (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 November 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Pedro Sánchez diluye a Pablo Iglesias con tres vicepresidencias más". ELMUNDO (in Spanish). 9 January 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ 20minutos (9 January 2020). "Sánchez trata de diluir a Iglesias nombrando otras tres vicepresidentas". www.20minutos.es - Últimas Noticias (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 November 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Doscientos años del Consejo de Ministros". La Razón (in Spanish). 20 November 2023. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ "Un error en el BOE rebaja la condecoración concedida al presidente de Italia". OndaCero (in Spanish). 11 December 2024. Retrieved 12 December 2024.

- ^ Confidencial, El (30 December 2011). "El Gobierno condecora a Zapatero con el Collar de la Orden de Isabel la Católica". elconfidencial.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ "El Gobierno condecora al Ejecutivo saliente con distinciones de la Orden de Isabel la Católica y la de Carlos III". Europa Press. 3 August 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ "Un título nobiliario para los ex presidentes de Gobierno". Diario ABC (in Spanish). 2 April 2004. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ a b c de Francisco Olmos, José María (2010). "The granting of Noble Titles to the Presidents of the Council of Ministers during the Restoration (1874-1931)" (PDF). Royal Academy of Heraldry and Genealogy (in Spanish).

- ^ "El Rey concede el Toisón de Oro a Adolfo Suárez". www.elperiodico.com (in Spanish). 8 June 2007. Retrieved 14 April 2024.

- ^ "Muere Adolfo Suárez, el presidente de la Transición". ELMUNDO (in Spanish). 23 March 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- ^ "El Rey nombra a Calvo-Sotelo marqués de la Ría de Ribadeo con Grandeza de España". La Voz de Galicia (in Spanish). 25 June 2002. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- ^ "Los que dijeron "no"". El Correo (in European Spanish). 5 February 2011. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ Office of the Prime Minister (8 August 1983), Real Decreto 2102/1983, de 4 de agosto, por el que se establece el Estatuto de los ex Presidentes del Gobierno (in Spanish), p. 21933, retrieved 19 November 2023

- ^ Office of the Prime Ministerio (4 May 1992), Real Decreto 405/1992, de 24 de abril, por el que se regula el Estatuto de los Ex Presidentes del Gobierno (in Spanish), p. 14993, retrieved 19 November 2023

- ^ DÍAS, CINCO (24 July 2004). "El Consejo de Estado supervisará la reforma de la Constitución". Cinco Días (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ Confidencial, El (28 July 2015). "Zapatero abandona el Consejo de Estado para presidir el consejo de una fundación alemana". elconfidencial.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ Manovel, Marina León (15 July 2023). "¿Cuál es el sueldo vitalicio que cobra Rajoy, Aznar o Felipe González después de ser presidentes?". elconfidencial.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 November 2023.